In this, the second post from our three part series on principles of voice design, I'll be discussing the principle encapsulated by the dictum "be contextual". In other words, a well-designed voice application should, as much as possible, individualize the entire interaction.

This post, and the series of posts of which it is a part, are based upon a talk I had the opportunity to give on November 28th with Paul Cutsinger at re:Invent. The first post in this series can be found here, and links to the recording and the deck from the re:Invent talk can be found here.

When people speak with each other, they tailor the conversations based upon context and what the other person says. Even something as simple as a morning greeting has a number of variations:

If somebody only used one greeting, it would seem odd, uncanny, and inhuman.

The ability a person has to contextualize and individualize a conversation is the major reason people have, for years, strongly preferred talking with another person on the phone rather than a computer. For a person to want to talk with a voice-interface, the interface needs to individualize the conversation as much as possible.

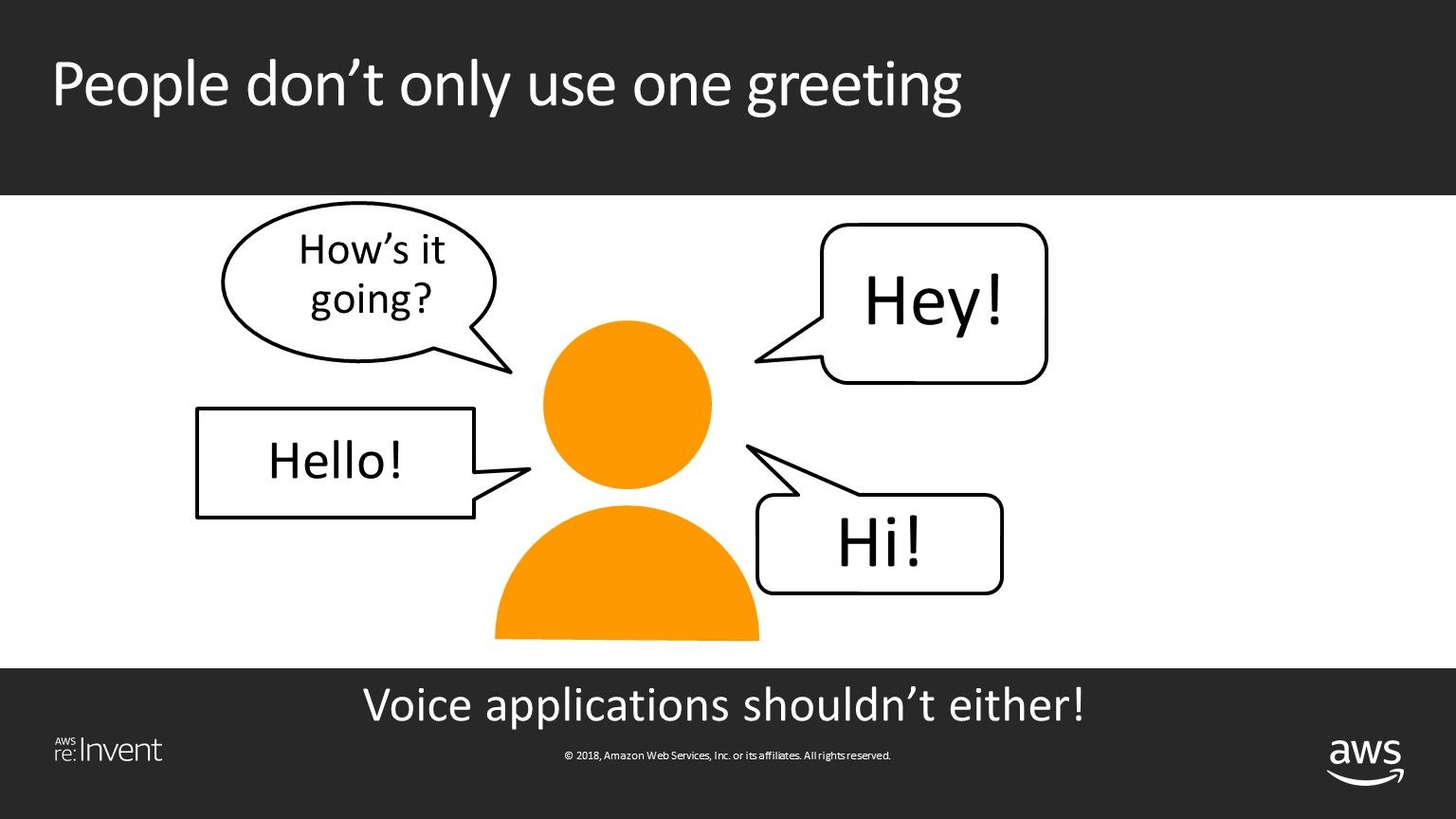

One of the simplest ways of introducing variation into conversational design is with random responses. However, random responses can be dangerous, as they fail to be contextual, and can produce awkward and/or confusing interactions. For example, Pulse Labs tested a quiz skill a while back, in which one tester went through the following interaction:

Asking the user if the questions are "too tough" doesn't make a lot of sense right after the user gets an answer right! The "Too tough?" response was random, and in this case, didn't make sense in context.

As the above example illustrates, even something as simple as a well-designed quiz skill requires a fair amount of contextual information. As an example of a quiz skill that does it right, the very popular and successful Jeopardy! skill not only stores the user's score for the game being played, but also the scores from all the user's previous games, the scores from Jeopardy! games played by other users that day, and the amount of time since the user previously played the game. All these data are used to individualize the experience, making it more enjoyable.

Now, it's not always easy to predict when, where, and how users will want individualization in their conversation, and the type of individualization they will want. One of the best ways to figure this out is through user testing with real world users, and the best place to do that is Pulse Labs!

In the third and final post in this series, I'll dive into the principle upon which voice design differs from visual design the most - a principle encapsulated by the dictum "be available".

I hope you found this post useful, and I look forward to seeing the contextualized voice applications you will build. Paul Cutsinger and I will be repeating our presentation from re:Invent at the 2019 Voice Conference in Chattanooga, Tennessee on Wednesday, January 16th at 10:30 AM (Session 224). We'd love to see you there!

Happy New Year!