On November 28th, I had the opportunity to present at re:Invent, Amazon Web Services annual conference, with Alexa evangelist Paul Cutsinger, on the the subject of "Alexa Skill Developer Tools: Build Better Skills Faster." You can find links to the recording and the deck from the talk here.

A major section of the talk was on principles of good voice design - and how they differ from design in primarily visual mediums like web and mobile. Paul has written a white paper on the subject that you can find here. I highly recommend it. I explored some of the principles from Paul's paper in the context of examples that we've seen in our testing. This post is the first in a three part series on these principles.

The first major principle of voice design is to be adaptable. You can't constrain users into responding with words and phrases that you expect, you need to let users speak in their own words.

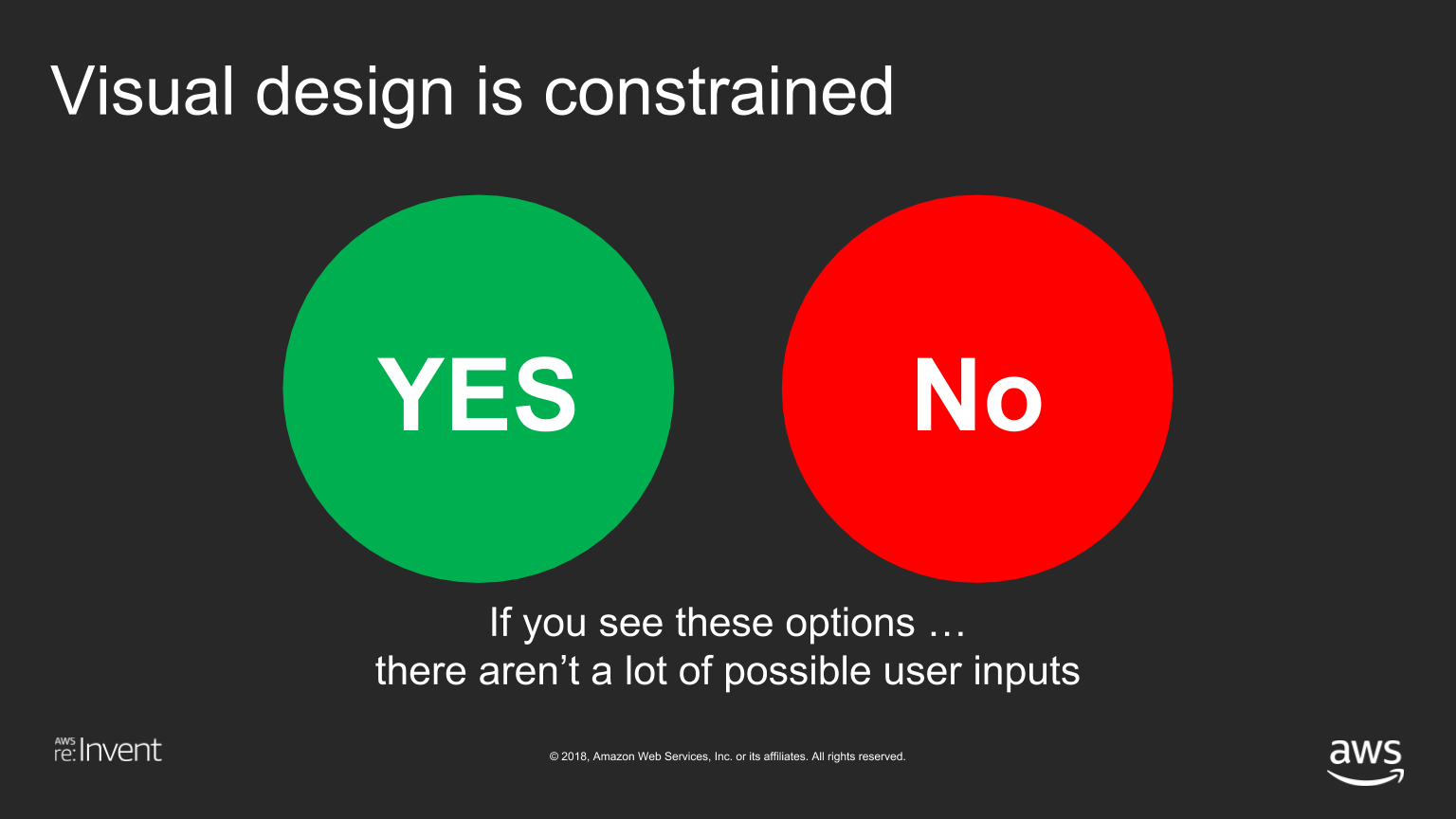

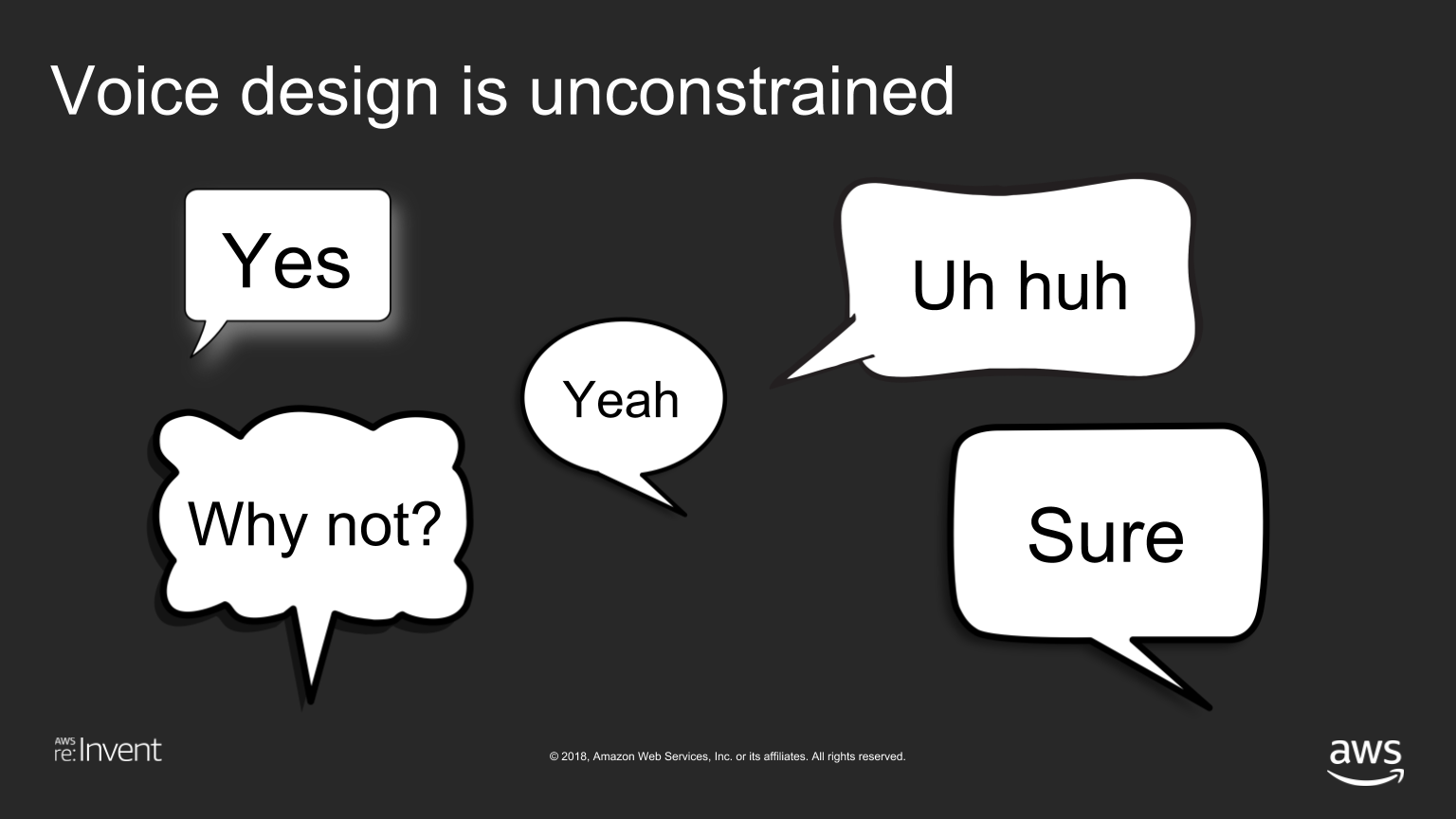

This is much easier said than done. For example, in visual design, user inputs can be constrained. As an extreme example, if you want the user to respond with "yes" or "no", you can just create two large buttons, and be pretty sure the user will pick one or the other.

In voice, however, even something as simple as "yes" can be communicated in many different ways.

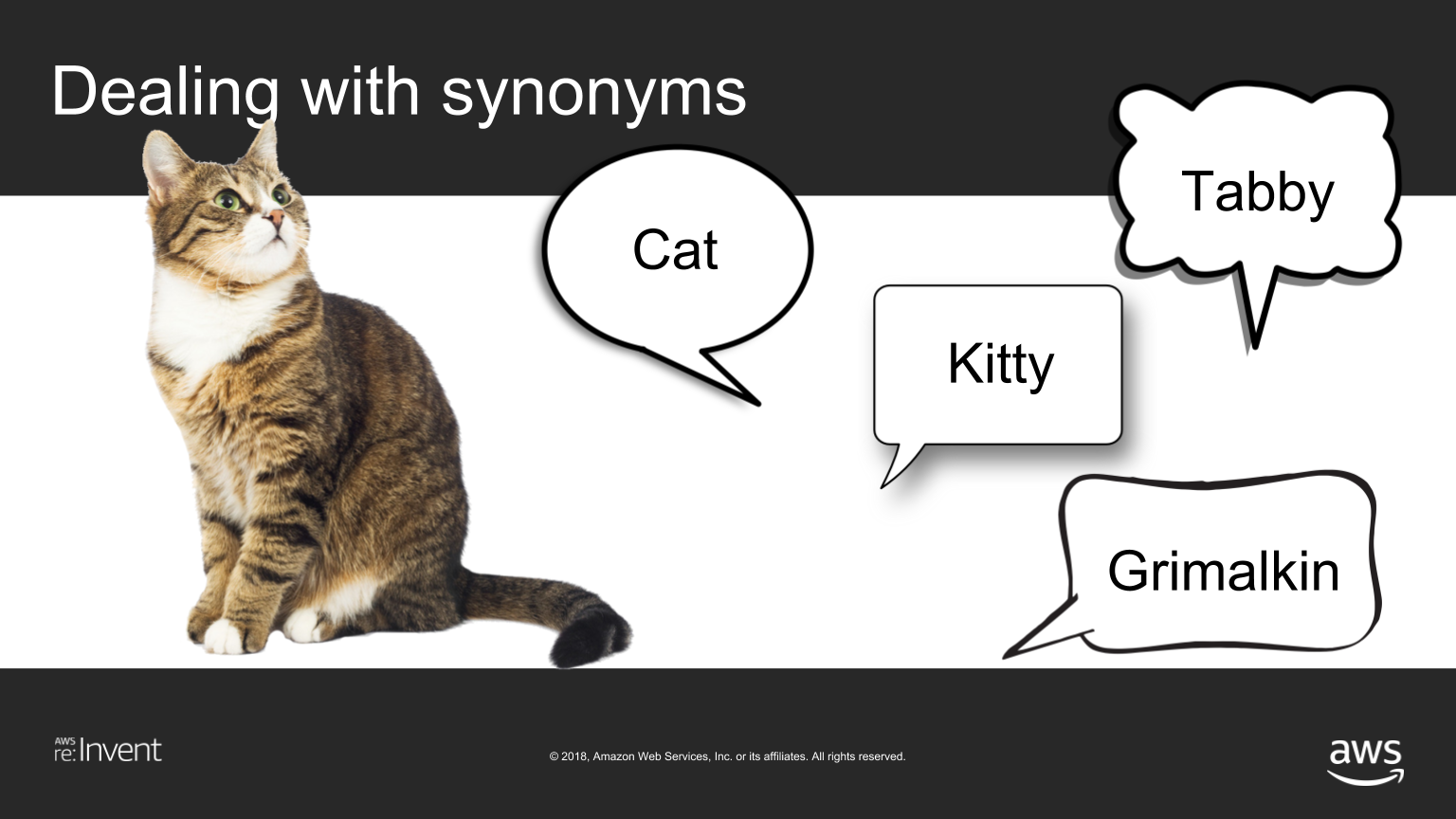

A well designed voice application needs to be prepared for all of these. Similarly, language is vast, and there are very frequently many different ways to say the same thing. Even something as simple as a cat can be referenced with many different English words.

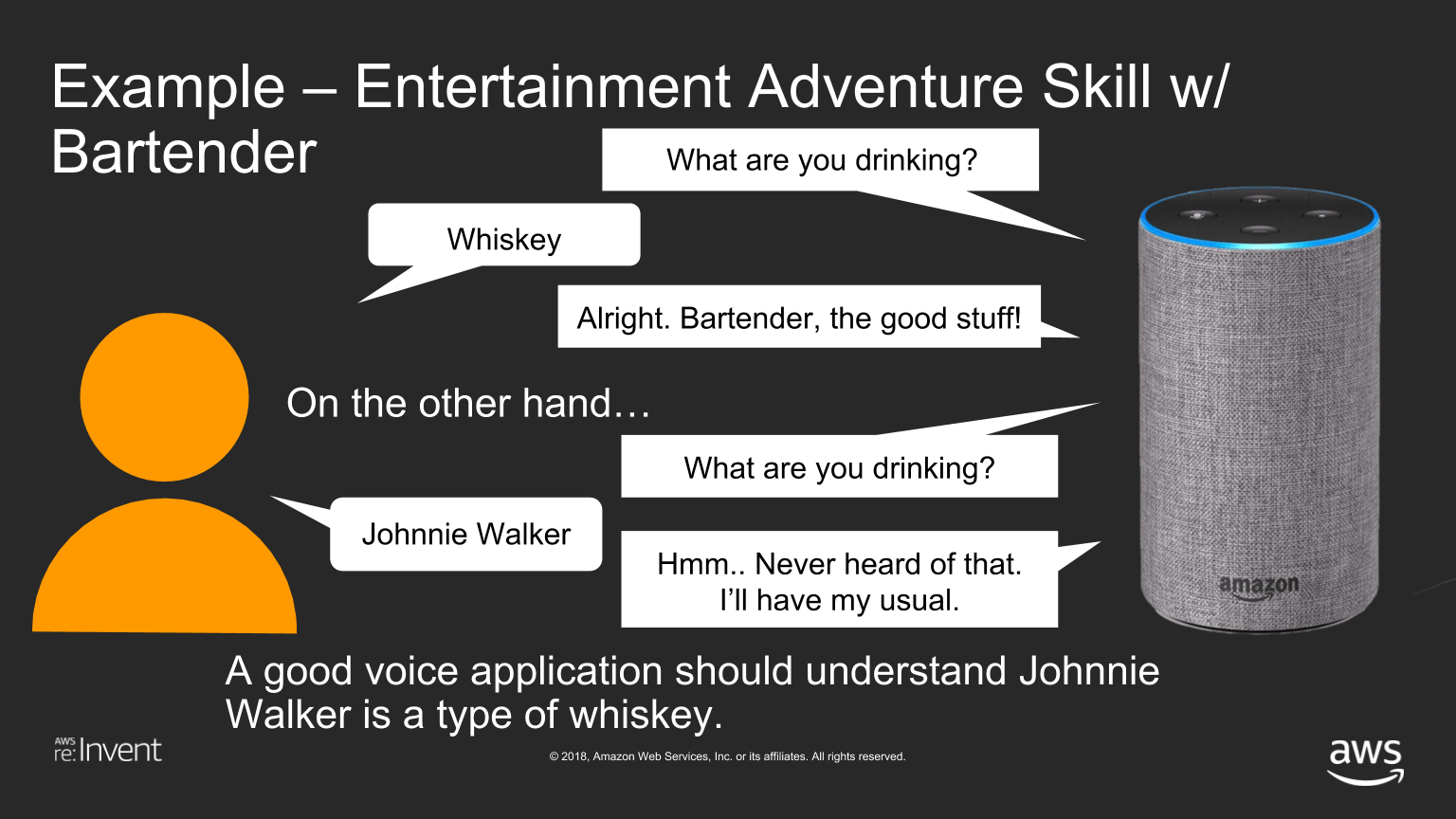

We saw this issue in an entertainment adventure skill we tested. The skill included a bartender, that responded appropriately if asked for whiskey, but didn't understand a request for Johnnie Walker.

A bartender who doesn't know Johnnie Walker is a pretty strange bartender. A well designed skill would not only understand "whiskey" here, but also most popular whiskey brands.

Of course, it can be very difficult, if not impossible, to figure out all the possible things your users will say, bet one of the most effective ways you can figure out a lot of them is by testing with real world users, and the best place to do that is with Pulse Labs!

I'll be exploring two other critical principles of voice design - "be contextual" and "be available" - in my next two posts in this series. I hope you'll find them useful as you design and build your own voice applications.

Paul Cutsinger and I will be repeating our presentation from re:Invent at the 2019 Voice Conference in Chattanooga, Tennessee on Wednesday, January 16th at 10:30 AM (Session 224). We'd love to see you there!